There's an Asian education conference going on this week. 'So?' most of you are probably asking. But it's interesting and this is why. All the things that are said about educating our children for the 'Asian Century' sound good and read well - but it's more spin than substance.

Now, let me declare that I might not know anything about this professionally, as I'm a maths teacher. But I do have experience of this as a mum, grandmum and aunt.

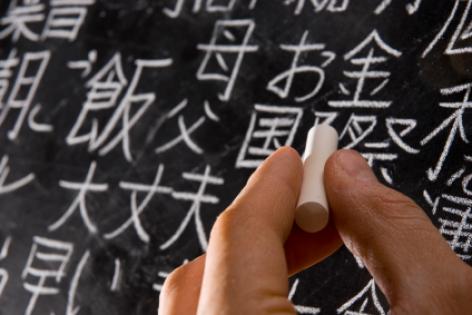

In case you're not aware, 'Asia and Australia's engagement with Asia' is one of the four cross-curriculum priorities in the national school curriculum.

The reason for this is obvious. Already accounting for around 70% of the world's population and a significant proportion of its wealth, many Asian nations continue to grow rapidly and are influential on a regional and global basis. The idea is that our children should understand the history, culture and languages of Asia to help build social cohesion with our neighbours as well as help build business links.

I teach in a school which is large. It's not particularly well-heeled, but it's not in a low socio-economic area either. The kids at our school have a choice of learning French or Spanish.

Spanish is useful. It's the second largest native language in the world.

But French? No disrespect to my colleagues who teach it - one of them is my best mate - but unless they're all going to work for the United Nations or an international NGO, it's really not that useful. Except for holidays if you want to show off to the French ... not that the French would be impressed at all.

One of my grandkids attends a school which offers Chinese and French. Another where German is offered. Another where it's French or Italian (Italian being even less useful than French, other than if your child wants to be an opera singer).

Surprisingly though, Italian is also a priority language for the Australian Curriculum and Reporting Authority (ACARA) on the basis that many Australians of Italian background speak it at home. The fact that less than 1% of the world's population appears not to matter to ACARA.

But, as I see it, there are two problems with all this talk about increasing Asian literacy.

- One, we don't have enough teachers who are qualified sufficiently to teach the new curriculum. This was borne out with the release at the Asian education conference this week of some data that reports on a self-assessment survey of 2,000 Asian language educators. It showed that less than one-third see themselves as being at least 'highly accomplished' as teachers of Asian studies or languages. It made the point - very politely - that it's difficult for kids in schools to learn about Asia if there are insufficient teachers to teach them.

- Two, anecdotally, the better skilled university graduates are getting jobs elsewhere - not necessarily because of money, but because despite what all the experts say, there are not the jobs around to employ them. I give two examples. Both are young Australians in their late 20s.

The first is a young woman who studied Chinese right through university, but also spoke it at home with her dad who is a fourth-generation Chinese Australian. For two years of her schooling, she lived in Hong Kong. She graduated in language and education; worked as high school teacher in Sydney, where 90% of the students studying Chinese were Chinese-born or first-generation. After spending a year travelling, she found herself a better teaching job (and a great lifestyle) in New York City. She says while she misses her friends and family in Australia, she also loves the fact that she feels "appreciated" as a teacher. Chinese is compulsory at the school she teaches right through to the equivalent of Year 10.

The other is a young man. He is highly qualified; speaks Bahasa Indonesian and Japanese fluently and - wait for it - he couldn't find a job here. He tried. He is intelligent, well-presented, well-spoken, very competent and a nice young man. But no-one in Australia had a job to offer him. So what did he do? Found a job in Japan, not teaching English but working in a Japanese company where he speaks, writes (and maybe thinks) Japanese all day.

I don't have an answer. These may be two solated cases but, if they are any guide to the challenges facing Asian literacy in Australia, they show up two issues.

We need to put some thought and action into getting the teachers who can actually teach our children Asian culture and language. We shouldn't lose young women like the one I mentioned because they feel under-appreciated as a teacher here (although I admit New York City would be an attraction for me if I was her age). And maybe it's about time Australian companies employed the young graduates who do have skills and experience in Asia so younger children can see that such education and living experience is actually appreciated and valued, and offer jobs that are worth aspiring to.

__small.png)