The recently released report by the Productivity Commission on Childcare and Early Childhood Learning is a "disappointment" according to a former pre-school manager and now academic, Dr Gerardine Neylon of the University of Western Australia.

"The report ignored what leading experts in education and early childhood from around the world believe - that the quality of early childhood services is vital," Dr Neylon said.

Numerous studies have shown that the first five years of a child's life is when 80% of brain development occurs.

"This sets the foundation for development and learning in later years. Quality early childcare sets up a child for school, and the learning habits they develop in these years can last a lifetime."

According to the OECD, countries should spend a minimum of 1% of GDP on early learning - but Australia lags its OECD counterparts due to historically low investment in the sector. The OECD average expenditure is 0.7% of GDP, while Australia spends 0.45%.

The Productivity Commission report did not recommend an increase in funding but instead recommended a system of existing payments be replaced by a single means-tested subsdiy called the 'early care and learning subsidy', to be paid directly to operators of childcare and early learning centres.

Dr Neylon says this is a "short-term, quick-fix approach."

"If implemented by the Government, it will not improve Australia's rating in terms of the OECD assessment.

"This report is a missed opportunity to build on the investment in quality of services made by the former government."

She said the new regulatory authority, ACECQA, is now visiting services, rating them and assessing how they can reach the National Quality Standard.

"The qualifications required of those working in the sector has also increased, which is all part of working towards improving Australia's poor childcare standing in the OECD."

Dr Neyon says that the report does not address the issue of bringing pay rates into the sector in line with those in the education sector with the same qualificaitons.

"Both teaching and early childhood education are worthy careers but they are worlds apart in terms of training, status and compensation.

"School teachers are employed in what is a traditional, relatively uniform and coherent system of services with well-established public funding support. But the early childhood education workforce operates within an unwiedly, cumbersome mix of services spread across the for-profit and not-for-profit sectors."

She says the report fails to address the issue of federal funding to recruit and retain qualified educators.

"Investment in the early childhood sector would have a lasting impact on the contribution early learning makes in shaping future national productivity and prosperity," Dr Neylon said.

Research carried out in the 1960s on children aged 3-4 years, randomly divided children into groups who received high-quality pre-schooling and a comparison group who received no pre-schooling. In the study’s most recent phase, 97% of the study participants still living were interviewed at age 40. The study found that adults at age 40 who had the pre-school program had higher earnings, were more likely to hold a job, had committed fewer crimes and were more likely to have graduated from high school than adults who did not have the benefits of pre-school as children.

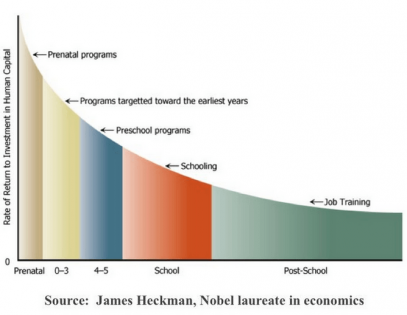

This research was built on by Nobel Prize-winning University of Chicago Economics Professor James Heckman. His ‘Heckman Equation’ (below) shows the great gains by investing in early learning.

__small.png)