She is worried about the risk of passing on a genetic mutation called BRCA 1, a predisposition to cancer that she has a 50 per cent chance of passing on to any children she may have.

At 36, she is relieved to know that if she does have children, she can use embryo screening technology to choose ones without the mutated BRCA gene to go on to pregnancy with.

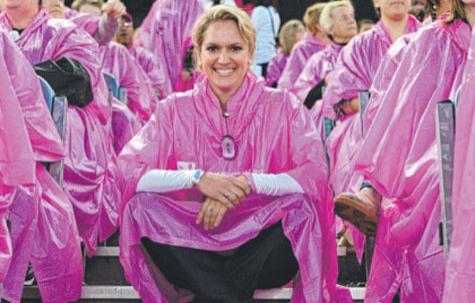

"I would certainly be looking on it as a positive option, definitely," Ms Burnett, of Perth, told AAP.

People with the BRCA mutation have a 60-80 per cent chance of getting breast cancer and a 30-60 per cent chance of getting ovarian cancer.

Ms Burnett survived the aggressive cancer after being diagnosed at 31.

She has also seen her grandmother die of ovarian cancer, her aunt die of breast cancer and her cousin diagnosed with breast cancer.

The preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) technology used for the embryo screening has been available for 20 years in Australia and is applied to a range of other illnesses, such as cystic fibrosis.

Melbourne IVF medical director Lyndon Hale said in the last few years it had been taken up in Victoria by a "handful" of fertile women, who would otherwise not need IVF assistance to conceive.

Dr Hale says it is logical that women with the BRCA mutation would wish to protect their children from facing the same risk of a potentially fatal illness.

"Here you have a family which has dealt with several breast cancers, now the person has found out they're carrying the gene themselves, they've got a 60-80 per cent chance of having breast cancer ...

"So they're dealing with a lot at this point in time and if they've still not had children then they're thinking, 'if I have kids, they're going to have exactly the same issues as I've got'."

Ms Burnett and Dr Hale both rejected any label of "designer babies" being attached to the BRCA screening.

__small.png)